How states can fight unreasonable college degree requirements

Plus: Trump's opportunity to fix student loans, and the college enrollment decline reverses.

Next month marks three years since then-Governor Larry Hogan of Maryland declared that his state would eliminate the four-year college degree requirement for thousands of jobs in the state government. Most state jobs, he argued, could “substitute relevant experience, training, and/or community college education for a four-year degree.”

Hogan stood alone at first, but he turned out to be a trendsetter. Half the states have now taken steps to remove degree requirements from state government job postings. “Skills-based hiring,” wherein employers judge job candidates based on their skills and competencies rather than whether they have a college degree, would do good anywhere—but especially in the state and local government sector.

State governments are likelier to require degrees for middle-class jobs

I examine the extent of degree inflation in state and local governments in a new report for the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP). Along a number of measures, state and local governments impose more questionable college degree requirements than private-sector employers.

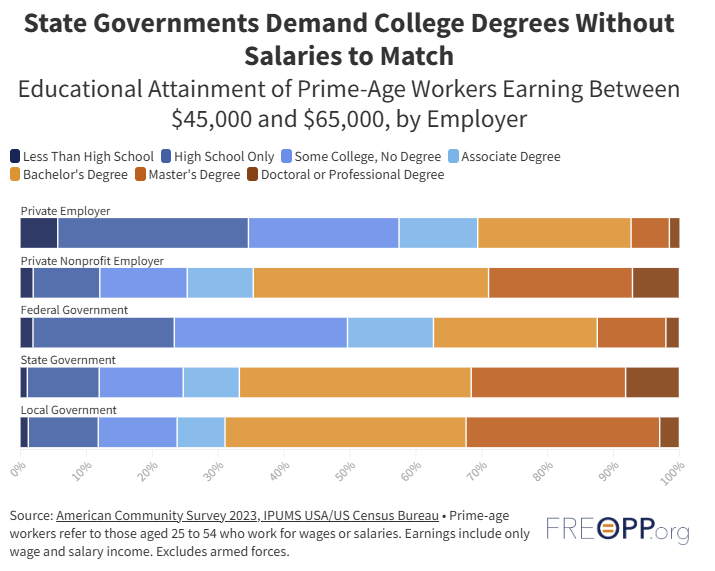

Consider workers in the middle of the income distribution: those earning between $45,000 and $65,000 per year. In the private sector, 31 percent of these workers have a bachelor’s degree or higher. But among state and local government workers, the proportion of middle-class workers with a degree is a whopping 68 percent.

State and local government workers also have higher levels of education than than their private-sector counterparts working in the same occupation. To be precise, people working in the state or local government are 39 percent more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree, conditional on occupation, than private-sector employees.

For instance, both private employers and state governments hire first-line supervisors of office and administrative support workers. But the degree requirements for this profession differ by employer sector. While only 36 percent of private-sector office supervisors hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, 50 percent of state and local government workers in this profession have a degree.

To be sure, there are differences in the sorts of work public- and private-sector employees perform. But the fact that state and local government workers are likelier to need bachelor’s degrees than private-sector workers earning comparable salaries and doing similar jobs should raise red flags that the college degree craze in the public sector has gone too far.

Will states make progress hiring workers without degrees?

State governments’ irrational preference for college degrees makes the skills-based hiring movement especially important in the public sector. But is it working? An early analysis of states that pursued skills-based hiring concluded that the share of government job postings with degree requirements fell by 2.5 to 3.1 percentage points for each year the policy was in effect. However, we can’t yet conclude whether this has translated into increased hiring of workers without four-year college degrees.

Dropping degree requirements is a good first step. But states need to take additional action to ensure that workers without degrees actually have a shot at the roles newly open to them. In this regard, one leader is Colorado. Governor Jared Polis was an early enthusiast for skills-based hiring in the public sector. His state also created an apprenticeship program to train up workers without degrees for state government roles. Colorado’s model has inspired a Council of State Governments-designed framework for other states that wish to create public-sector apprenticeship programs.

Unnecessary college degree requirements close job opportunities to the six in ten Americans who lack a bachelor’s degree, and make it harder for state governments to fill open jobs. Leaders like Hogan and Polis have recognized that states are disproportionate contributors to college degree inflation. But they also have unique power to fix the problem.

What I’m writing

How Trump can fix the federal student loan program. (Washington Examiner) Student loans are a mess—and one big reason is that the federal government happily lends money to students enrolled in degree programs that are unlikely to provide a return on investment. To fix this problem, President Trump could direct his Education Secretary to exercise her statutory authority to “provide for the implementation of a quality assurance system” for colleges participating in the student loan program. Schools would have to meet minimum quality benchmarks or lose access to loans. Such a move would prevent millions of students from taking on bad debts, and save taxpayers billions.

Four college enrollment trends to watch. (AEIdeas) After initially reporting a drop in college enrollment, the National Student Clearinghouse now figures that student numbers increased in fall 2024. But it wasn’t even across the board: vocational schools and high-value college majors like nursing and engineering showed strong growth, consistent with students waking up to the reality that not all higher education is equally valuable (at least from a financial perspective).

What I’m reading

American students’ math and reading test scores dropped significantly in 2024, my colleague Nat Malkus writes. But even more striking was the growth in the “achievement gap”—while high achievers’ scores held steady, for low achievers, the bottom fell out.

Is it time for the federal government to get out of the student loan business? Andrew Gillen of the Cato Institute thinks so—and offers a framework to do it.

Some Utah lawmakers want to set aside part of the higher education budget to fund high-ROI degrees, reports the Utah News-Dispatch, and close programs with low enrollment—some of which graduate just one student per year.

Graduates of top business schools are struggling to find jobs, reports the Economist. The share of elite MBA graduates who find jobs within three months is now 84 percent, down from a 92 percent average over the past five years.

The National Institutes of Health made news with its new policy (which a federal court has blocked) to cap overhead costs for research grants at 15 percent. Jay Greene of the Heritage Foundation defends the move, noting that some universities charge taxpayers over 60 percent for overhead.

What I’m doing

Hilary Burns of the Boston Globe used my research on college return on investment (ROI) to report on the ROI of college degrees in New England.

I visited San Diego in January to speak at AEI’s faculty summit. I also got the chance to go scuba diving with sea lions in nearby La Jolla. I captured my experience in the photo below (in case there’s any confusion, this is the sea lion dive, not the faculty summit). More pictures here and video here.